It happened again.

It feels like every few months I have a video game op-ed shoved in my face wherein the writer loudly proclaims that they don’t “get” roguelike games. For the life of me, I don’t know what it is about roguelikes in particular that provoke this kind of response in people. There are plenty of genres I don’t personally get much satisfaction from. RTSs, simulation racers, movement shooters, the list goes on, and I don’t think there’s anything surprising about that. Nowadays it’s pretty accepted that most gamers have their “genres.” The NES wizard who masters every game that comes out just isn’t a person who exists anymore. So, usually when people don’t “get” a game genre is suffices that it’s just a matter of taste…except when roguelikes are concerned, for some reason. Fighting games, in large part, are a genre catering to a very specific audience with very specific desires, but I haven’t seen a random game pundit go full George Wood Mode on a fighting game in quite some time, because it’s something that’s just understood. Yet, something about people’s inability to appreciate roguelikes seems to symptomatically coerce them to make it my problem, so here we are.

The article in question comes from Polygon, and is titled “Roguelikes are my natural enemy and I need to understand why you all like them,” lest you thought I was exaggerating in any way with the above paragraph. It makes the usual points. These games are too hard, permadeath is too punishing, I need my cheevos, etc. I could pick apart the article (and I will return to one particular line that bothered me later on), but I’d rather take this in a more constructive direction. I’ve been issued a challenge. This writer asked me to explain why I like roguelikes, and that’s what I’m going to do.

Roguelikes are my favorite genre of game. They have been since I first downloaded Nethack in the late 2000s. I’ve put more hours into Binding of Issac than any other game on my Steam profile, and roguelikes (and lites) easily make up over half of my overall library. I love proc-gen in all its wild and unpredictable forms, and if a game exists with a “roguelike” “rogue-lite” or “procedural generation” tied to it, there’s a good chance I’ve at least given it a peek.

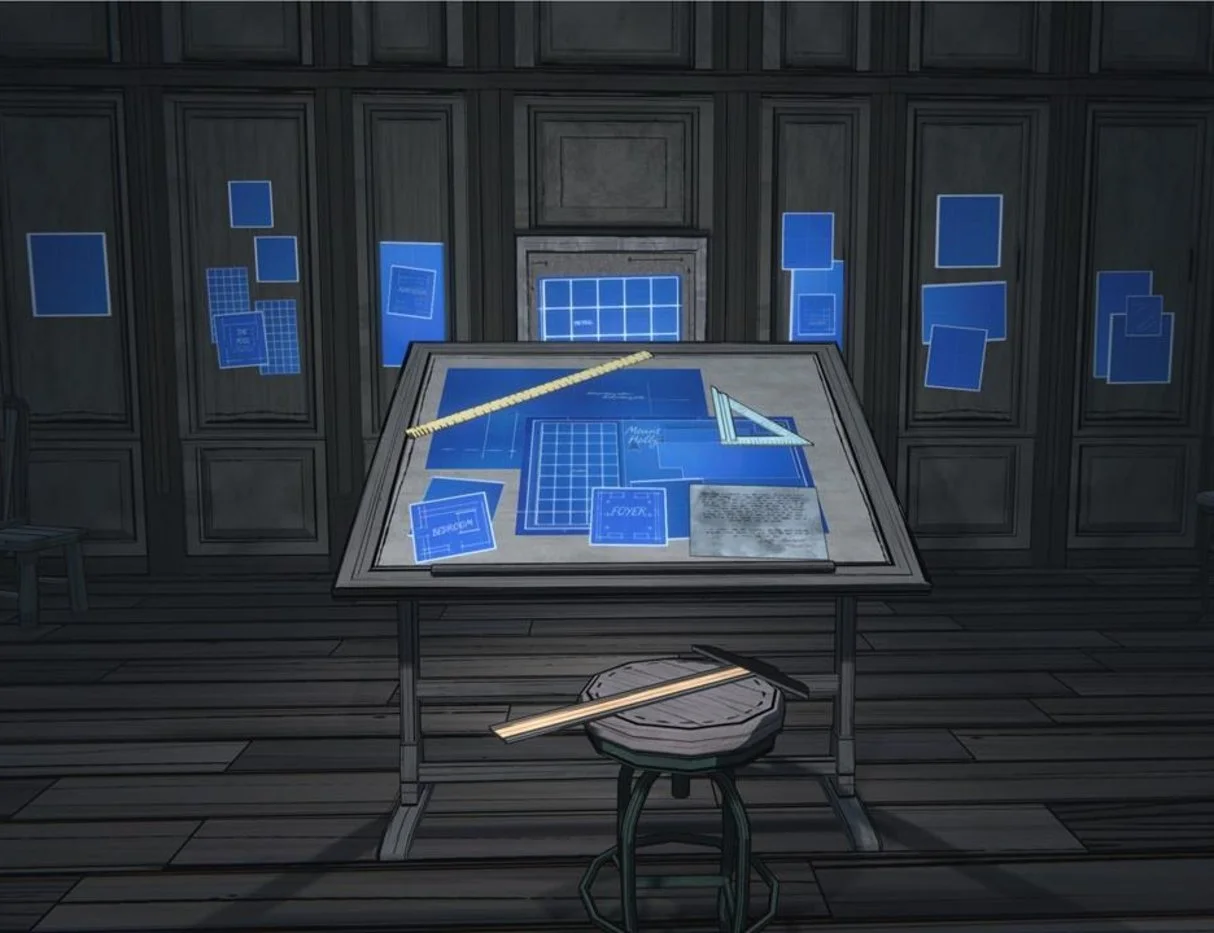

So, why? What keeps me hooked? Why do I play so damn many of these games? What about this genre has made it so appealing to my brain that, when it finally came time to make my first commercial game, I couldn’t help but make a roguelike of my own?

A few reasons.

REASON 1: A GAME THAT’S DIFFERENT EVERY TIME

Back when I was about seven or eight years old, I got to talking with a friend of mine about the game Link’s Awakening for the Game Boy. It had just come out, and I’d been thinking of asking for it for my birthday, so my friend was explaining some of the mechanics of how it worked. He mentioned cutting grass and bushes for resources, and something he said stopped me in my tracks.

“When you cut a bush, the stuff that comes out is random. So like, it’s gonna be different every time you play the game.”

My mind reeled. Was that really possible? With enough random elements, could Link’s Awakening really be a new experience every time I played it? I was only familiar with largely deterministic games up to that point, Kirbies and Marios and the like. Those games never changed. Everything was always in the exact same place, but…what if they weren’t? What if they were always different? Then the game would never get boring no matter how many times I played it! It…it would be the best game ever!

I would get Link’s Awakening for my birthday, and while I loved it, once I had the game in my hands I realized that the random grass drops didn’t do much to radically change the structure of the game. But, that idea of “A game that’s different every time you play it” never left me. I’d had a flash in my mind of the best game ever, and when I finally discovered roguelikes some ten-ish years later, it felt like literally finding the games of my dreams.

The promise of a game that’s different every time you play isn’t just the endless novelty, but also the endless ingenuity that it demands. You can’t simply follow a walkthrough or look up the answers online. Every adventure presents you with challenges the specifics of which no one has ever seen but you. It’s up to your knowledge of the mechanics, your resourcefulness in using what’s available to you, and your reflexes in thinking on your feet (if it’s that kind of roguelike) to pull you through. There’s a thrill to knowing you’re seeing things no one else who’s played this game has ever seen and doing things no one else has ever done, simply because the billions of possible seeds mean every single run is unique to you. Obviously there are limits, and depending on the game, you might hit those limits sooner rather than later, but the point remains. It's exciting to never know what’s around the next corner.

Practice in a roguelike isn’t about memorization, it’s about understanding, which leads into the next point.

REASON 2: WORLDS MADE OF RULES

A game of klondike solitaire is played with 52 cards. In video game terms, that means the game of solitaire has 52 unique pieces of content in it. The rules of solitaire arrange these cards, and this arrangement determines how the game can play out based on its rules. From 52 cards, that comes out to 8*10^67 possible starting states of solitaire. That’s eight followed by 67 zeroes. From 52 pieces of content, you get more possible games than could have possibly been played in the known lifespan of the universe.

And this…is beautiful.

Roguelikes aren’t built like other video games. Being “procedural” demands that the game’s elements and systems all talk to each other. A static level designer might create an aesthetically-pleasing space and then figure out what all the elements “do” afterward. A procedural level designer figures out what everything does, and the design emerges from how “what everything does” interrelates with “what everything else does.” Think again about a game of solitaire. The cards are simply numbers, letters, and symbols, but the rules determine both how they behave and how they allow other elements to behave.

A patch of ice makes enemies slip. Enemies that slip into walls take damage. A patch of ice next to a wall, therefore, is a trap, an identity that belongs neither to the ice nor the wall but how the rules of the game state the two interrelate to one another. How long until you, a player, see a patch of ice next to a wall? Will you know what to do when you see it? Maybe not the first time, but maybe the second, maybe after slipping into a wall yourself. It’s not just about memorizing where the ice traps are, it’s about understanding what the ice traps are. Then maybe, when you need to break open a rock but haven’t found a pickaxe, you’ll look over at that patch of ice and wonder if that will inflict enough damage to do the job. Only one way to find out. Either way, you’ll understand this work a little better.

Roguelikes are worlds made of rules, hidden rules you slowly learn by poking and prodding and experimenting. They’re worlds you don’t just look at or memorize, but learn to understand, fundamentally. It’s the same joy as an immersive sim, but without the ability to memorize the map, you’re forced to actually apply what you know in dynamic and uncharted situations. It’s thrilling!

But not as thrilling as…

REASON 3: THE BUILD

What I’ve said so far applies to more than just roguelikes. Any procedural game, your No Man’s Skies or Diablos 4, offer similarly intrepid treks into the RNG Frontier. So what is about the capital-R Roguelike experience that draws me? One word and definite article. The Build.

Something I weirdly don’t see many roguelike-haters talk about, possibly because they never played the games enough to know, is that roguelikes are short. A full run of Binding of Isaac takes in the area of 60-90 minutes depending on what you’re doing, and that’s the whole game, start to credits. Some games have shorter runs, some games have longer runs (and some games have runs that are, frankly, too long) but these games are meant to be short and ultra-sweet, as they condense the full RPG experience into a quick, arcadey run.

There’s a Katamari Damacy-like visceral joy to the way roguelikes quickly build your power over the span of your short run. You start as a small ball rolling up thumbtacks and 15 minutes later you’re consuming the Tokyo skyline. So it goes with roguelikes, which let you experience the full power growth of an 80-hour RPG in roughly 1/50th of the time. Every upgrade you find feels big and meaningful. Every choice you make has huge implications for your run, and since these are short games designed to be replayed over and over, they can make you commit to big, interesting build decisions. You’re never encouraged to make a boring do-everything character. You’re encouraged to specialize, be unique, synergize, experiment! Then start it all over and try something else! You’ve got an hour to kill, right? What happens if you only put points in Jump Distance this time?

Getting that first equipment drop in a roguelike is always a magical moment, because it’s when the gears start turning for how you’re going to build yourself this time. A fire wand? Guess I’m a fire mage! A potion kit? Huh, never really engaged with the alchemy system before, but maybe now’s the time. Spiked armor? Hmmm, if my defense was high enough, I wonder if I could get through encounters on the spike damage alone.

When I die in a roguelike I’m never dejected. I’m excited, because I get to have that moment all over again! I tried the crazy alchemist build, and I couldn’t quite get it to click, so let’s see what the next run has in store for me! But…oh.

I mentioned it. I…brought up the thing.

I guess…now we have to talk about it…

…the reason people hate roguelikes.

REASON 4: DEATH

So, I said there was a line in that Polygon article that I wanted to come back to, and it’s something that’s been stuck in my head ever since I read it because it just…felt so wrong.

“[The] whole concept of a subgenre that requires me to play continuously and, when I die (because I am going to die), have none of it matter makes me want to set myself on fire.”

Reading this line brought a lot of things into perspective all at once. As a roguelike fan, I’ve often wondered why permadeath was such a hangup for people. Like I said, these games are only about an hour long, and everything about them from their procedural nature to their focus on divergent builds is designed around making replaying them as fun as possible. What does it really matter if you live or die? Your run ends either way, and the real fun is in the starting over, seeing more and learning more and trying more. You always walk away with a story and a unique experience.

That is unless…none of that matters to you…because you didn’t…”win.”

And with this, I finally understand the problem. If you just look at games as objectives to be completed, or boxes to be ticked off, I…suppose a lot of the backlash against roguelikes makes sense. The game being different every time makes it harder to “solve” and therefore more frustrating. The hidden rules just feel like traps if all they do is keep you from “winning.” The endless builds just feel like distractions if you only care about the “right” one. And permadeath…well, it’s just lost progress. Nothing more.

Nothing that matters, anyway.

If that’s truly how you feel, I…don’t really know how to change your mind. I’ve told you why love roguelikes and, I suppose, it’s all the reasons you don’t. But, I will say this…

Playing video games is an inherently unproductive activity. You don’t “get” anything, and you don’t walk away from a video game with anything of value to “show” for it, win or lose. You won’t hit a higher tax bracket because you 100%’ed Final Fantasy VII Rebirth. Your records in Neon White won’t get you into a fancy club. And no matter how many roguelikes I beat, none of them are going to put food on my table. These activities are not productive.

But that’s true of all art.

You don’t engage with art because it gets you something, you engage with art because it does something to you. You don’t “beat” Citizen Kane, you experience it. It’s not the credits that matter, it’s all the stuff you saw along the way. Taking in art enriches the mind and soul. It inspires us, allows us to create our own art, and in turn inspire others. Every moment we’re alive weaves itself into the tapestry of who we are, and experiencing art dyes that tapestry with vibrant colors that bleed across the fabric and give us our lively patterns.

And all of that matters.

Video games present us with objectives. Win states and loss states. Paths, endings, achievements. But these are just the shape of the thing. Games have endings and objectives because they need to in order to be games, but it’s what you do on the way to those endings that’s important. That’s the experience. That’s the play. What’s the point of checking a box if you don’t remember how you did it?

As a game designer, as an artist, and as a roguelike fan, reading the words “when I die (because I am going to die), have none of it matter” hurts me. Because, if none of it matters when you die, none of it matters when you win, either. It’s the same game, either way. The same deck with the same cards. The same hour of your life you’ll never get back.

But isn’t it kinda magical, just looking at those cards, arranged in a shape that no one else has seen since the dawn of the universe?

Aren’t you curious what the next shape might be?